HELIX

FROM THE IDEA TO THE PRODUCT THE CREATION OF A SPECIAL LUMINAIRE

"Making something appear very simple, even though the design, production and, in particular, the details are highly complex, is a very special challenge for the planners and the manufacturing company." Klaus Adolph.

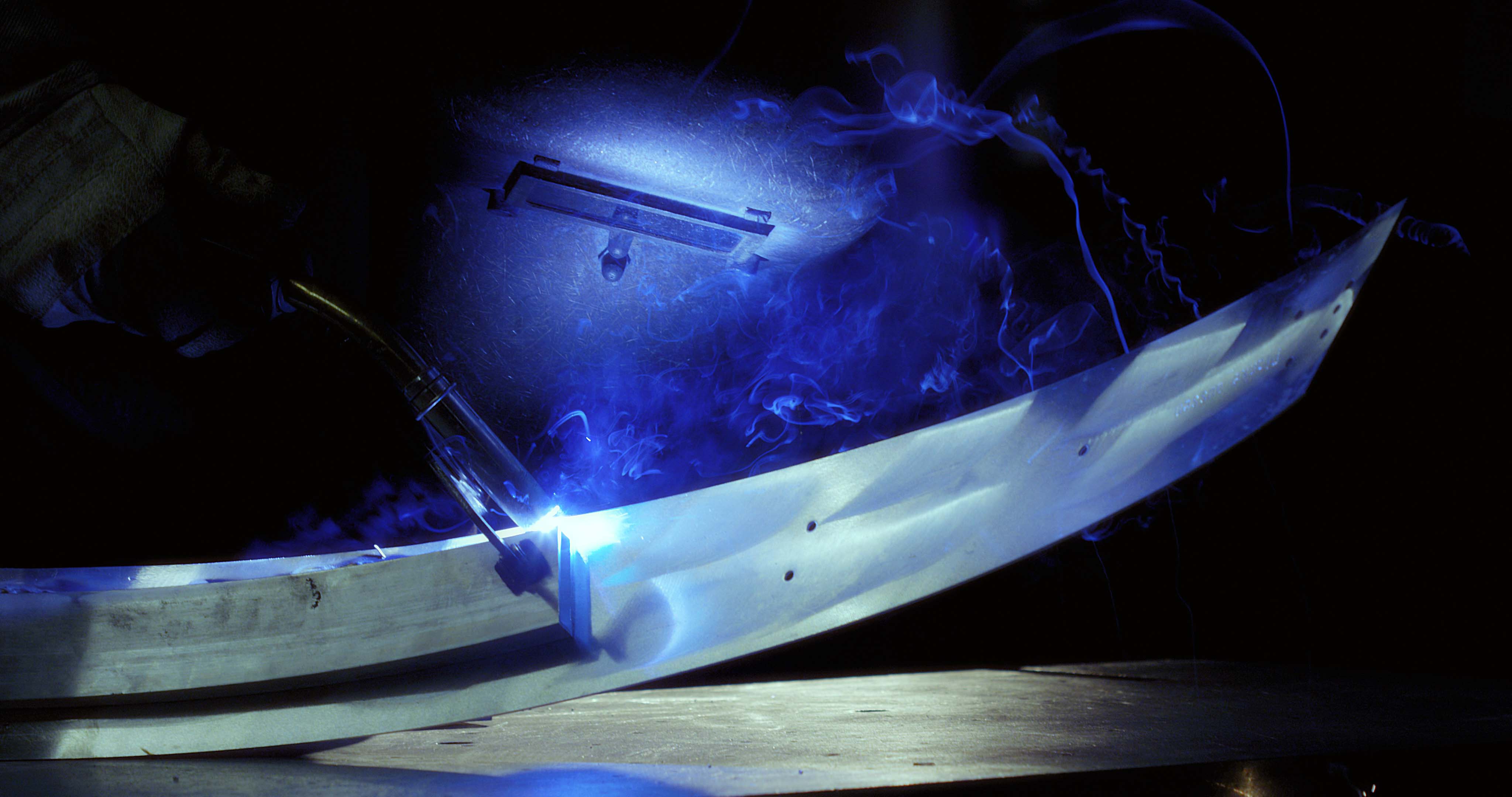

This describes our approach when working with lighting designers and architects. The Helix is the unique result of craftsmanship, attention to detail and constructive cooperation - reduced in appearance, with plenty of room for associations.

DEMANDING ARCHITECTURE NEEDS SPECIAL SOLUTIONS Interview with lighting designers Klaus Adolph and Tom Schlotfeldt, published in "Licht" magazine

RSL wanted to present itself to the public for the first time at Light+Building following its takeover by the Oligo Group and comprehensive revitalization. For this presentation, you had jointly designed a unique luminaire and accompanied the constructive development. What kind of luminaire was it to be? KLAUS ADOLPH: It was to be a special luminaire in the form of a double spiral. We had lots of ideas and ultimately decided on this simple shape that everyone would understand immediately. TOM SCHLOTFELDT: The shape is simple, but highly complicated to produce. There are many associations, such as with the filament of a light bulb, which brings us back to the RSL profession. You could describe the luminaire as the manufactory's DNA. It demonstrates the quality of the company's design, lighting technology and craftsmanship.

Are special designs still needed in the project at all, or do the brand manufacturers now cover every requirement with their sometimes very extensive product families? TOM SCHLOTFELDT: Special designs are definitely needed. If you think about the masses of luminaires on the market, you might think they cover everything. But that's not the case. Every project is unique. We need individual solutions for the architects we work with as lighting designers and in the architectural language in which we operate. Most manufacturers, where everything is geared towards series production, cannot provide this. That's why I'm delighted that there is now a living RSL again, with which you can realize manufactory solutions. They support the uniqueness of the architecture and make it more valuable.

You have also designed luminaires that RSL has designed and built in the past. Can you give some examples to explain the reasons for designing special luminaires in these cases? KLAUS ADOLPH: One of our first projects in Hans Theo von Malotki's office was the chamber music hall for the Beethoven House with the Cologne architect Thomas van den Valentyn.

How do architects and clients feel about special lighting solutions? Does it take a lot of persuasion? KLAUS ADOLPH: It's usually a spontaneous idea to do something special in the stairwell, entrance hall or conference area. You quickly get a yes or no from the architect. TOM SCHLOTFELDT: It varies. Of course, it also depends on the budget. One positive example is a very nice project that we have just been able to realize together with RSL. We designed large-format ring lights for the exterior of an important project, for which we received immediate acceptance from the client and the architect Nikolaus Goetze from gmp.

Mr. Adolph, you just mentioned spontaneous ideas. Is it mostly these flashes of inspiration when you approach a design, or are there also lengthy processes for finding ideas? KLAUS ADOLPH: That varies. There are several possibilities. The flash of inspiration can lead to the idea being carried through to the end. That everyone sticks with it. But it can also be that you realize at some stage that you're wrong. The project develops, you get involved with it yourself and at some point you realize that the lighting object is becoming far too important in the context of the architecture. Then we have to take a step back. Another approach is to go forward step by step with the architect. In my concepts, the object usually has something to do with the architect's ceiling design. We have realized many projects in Asia with von Gerkan Marg und Partner: opera houses and congress halls. At the beginning, you don't even know what the ceiling will look like. There is only one room on the floor plan. The acoustician largely determines the proportions of the room. There can be no flashes of inspiration. In such cases, a lighting object or the ceiling as such can only be developed step by step together with the architec.

Mr. Schlotfeldt, can you give us an example of how the design was done step by step? TOM SCHLOTFELDT: That was the case with the harbor promenade project in Hamburg with Zaha Hadid Architects. Step by step, we developed the designs for the slanted light poles, which evoke associations with reed stalks in the wind or boat masts, and coordinated with each other at every stage.

Special solutions harbor the risk that the lighting effect is de facto different from what was imagined at the design stage. What do you do as a planner and what does the manufacturer do to counter the thrill? KLAUS ADOLPH: If we as planners develop a lighting object with a manufacturer, accompany the individual steps and respect each other in our collaboration, this hardly ever happens. The risk minimization for both sides really lies in the support of the project by the designer. How does a company that implements your designs need to be set up? TOM SCHLOTFELDT: I can best explain this using the current practical example of RSL. Robert Hörstrup, who is responsible for the operational business of Oligo Lichttechnik and RSL Lichttechnik within the Oligo Group, is our main contact for the development of the double helix, which has not yet been completed. He is where all the threads come together. He is a very reflective discussion partner with whom we can discuss designs in a concentrated and calm manner. KLAUS ADOLPH: Mr. Hörstrup always got the employees on board. Just like in the good old days at RSL. Depending on whether our question related to the surface, the bendability of the material, painting or planking, we discussed it in the workshop with the employees who had the most know-how. That was simply great fun. TOM SCHLOTFELDT: There was mutual appreciation at all levels. That is rare. Things are often a little rougher in the construction industry. But the human components are very important. That's why it's great that there is once again a high-end forge like RSL, with whom you can implement these fine projects. The employees think about the details and get involved. A series manufacturer usually can't do that. It has to be someone who can supervise the project and is prepared to accept a longer development period.

Is your lighting design included in the construction process right from the start? TOM SCHLOTFELDT: The strange thing about lighting design is that it is incredibly important for the architect and client, but is nevertheless often forgotten or comes right at the end. Then you sometimes have to hurry and need a reliable manufacturer, a speedboat, to implement it. The interview was conducted by Petra Lasar

RSL Lichttechnik GmbH

Tannenweg 1

53757 Sankt Augustin